Building for the Margins

“Mental health is a term that’s been heavily stigmatized,” says Raj Mariwala—director of the Mariwala Health Initiative (MHI). Prior to when Raj and Harsh Mariwala set up MHI in 2015, funding for mental health initiatives had been quite limited. “In fact, people explicitly warned us not to use the term ‘mental health’ in the name of our organization because of the baggage and negativity that surrounded it,” says Raj. When Harsh Mariwala stepped down from chairman of Marico, the duo started MHI – an organization aimed at supporting quality mental health services, enabling ongoing research, and encouraging innovative, culturally sensitive, and inclusive community-based interventions.

When talking about MHI’s work Raj stresses that “mental health is a development issue, and we cannot neatly separate it from issues such as homelessness, poverty, and food security. These issues have very real mental health consequences; in fact, they share a bidirectional relationship.”

LGBTQIA+ Lens in Philanthropy and Mental Health

MHI has always aimed to unearth mental health narratives that have historically remained invisible. According to Raj, “When the more visible narratives are the privileged ones, we tend to uphold certain frameworks that leave behind those who have been historically marginalized.”

MHI strongly advocates for the adoption of an LGBTQIA+ lens in both philanthropy and mental health. This means centering the experiences of LGBTQIA+ individuals and understanding the unique stressors they experience. Raj explains that historically, they have been subjected to violence from mental health and releated disciplines. For example, homosexuality was classified as a disorder in psychiatric manuals until as late as 1990, leading to practices such as conversion therapy and institutionalization as standard forms of “treatment” for queer individuals. Adopting an LGBTQIA+ lens, which acknowledges such historical discrimination and seeks to learn from their lived experiences, is a crucial step towards making mental health services and support accessible to people from the margins. Raj emphasizes that this transcends the mere establishment of these services; it pertains to their usability, approachability, and appropriateness for the users.

Elaborating on this lens, Raj distinguishes between 'queer friendly' and 'queer affirmative' approaches in mental health. A queer friendly practitioner maintains a neutral approach in the therapy room and may not fully understand the experiences of LGBTQIA+ individuals who experience discrimination, stigma, and stress on the very basis of who they are, compared to their heterosexual counterparts. In contrast, a queer affirmative practitioner not only acknowledges these deep-rooted inequalities but strives to address the discrimination faced by LGBTQIA+ individuals. Such practitioners demonstrate active allyship and advocate for LGBTQIA+ individuals in different spaces.

Building Mental Health Awareness at Women's March 2018

How MHI is fostering an environment of accessible, affirmative, rights-based and user-centric mental healthcare

Leading by Example

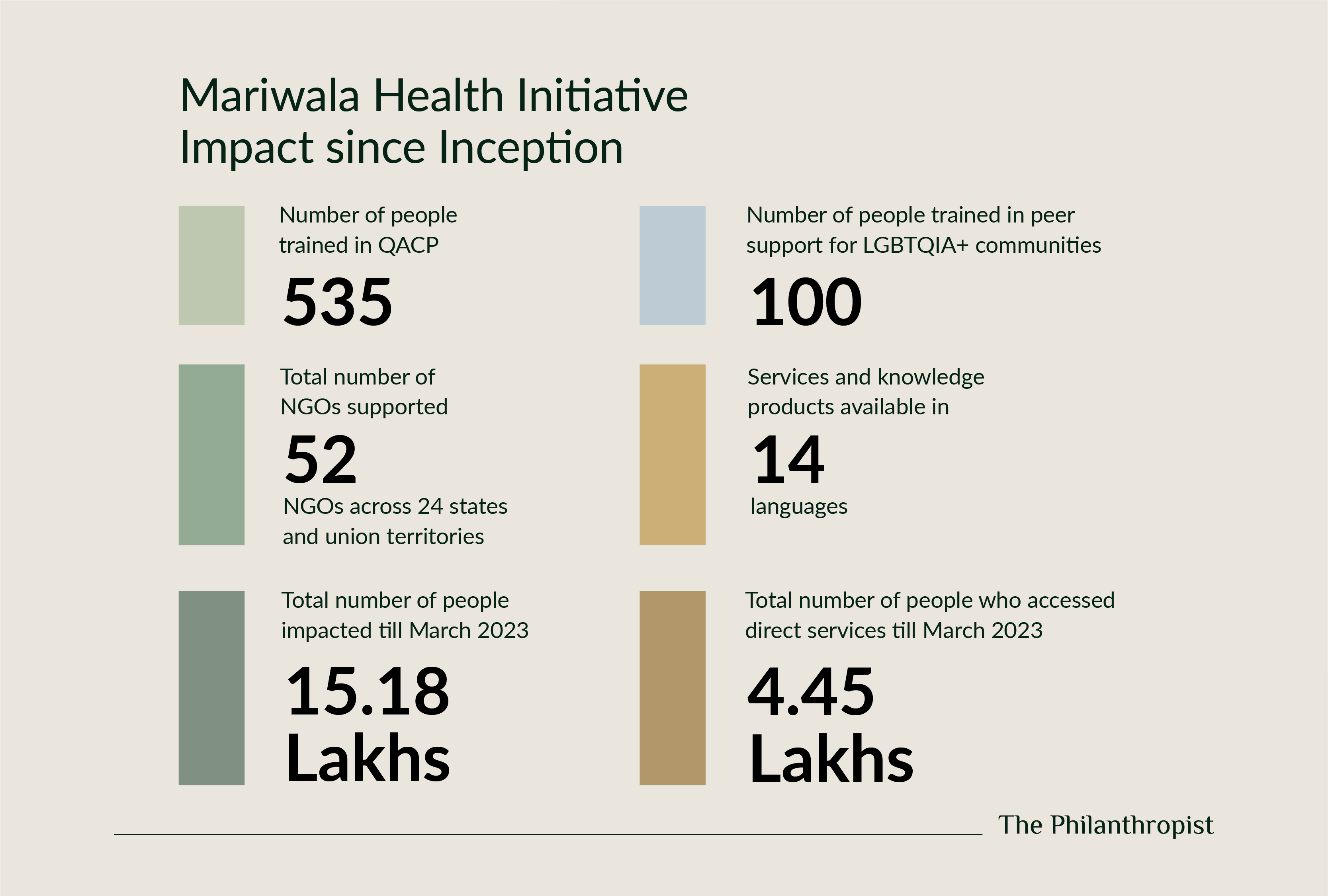

To foster a queer affirmative approach among mental health practitioners, MHI established their Queer Affirmative Counseling Practices (QACP) course in 2019—a 6 day program designed by queer and transgender Mental Health Practitioners (MHPs) that trains MHPs to be queer affirmative. Since the course’s inception, MHI has trained 535 MHPs under QACP. Additionally, 100 individuals have been trained in providing peer support for LGBTQIA+ communities.

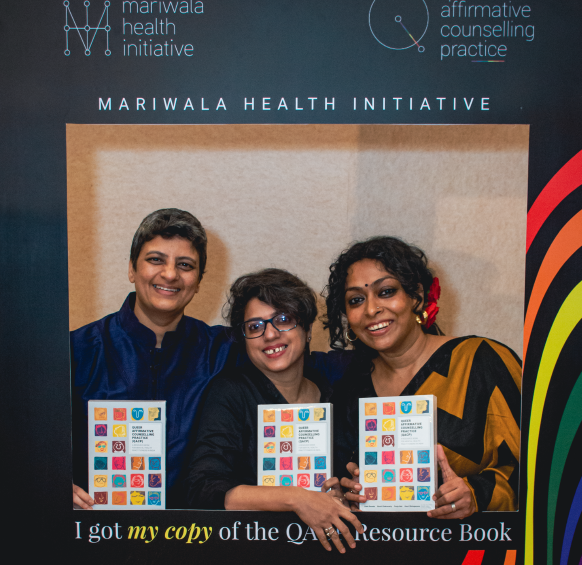

In 2022, MHI also launched the QACP resource book, which aims to help MHPs in identifying and addressing the unique stressors faced by LGBTQIA+ persons as they navigate through challenges faced in institutional, social, and individual settings. The resource book presents a well-balanced blend of knowledge, perspectives, skills, and a diverse array of pedagogic tools to engage with its content, which is rooted in the lived experiences of queer and transgender realities. This valuable resource can help MHPs in deepening their understanding and responding in affirmative ways to the unique challenges encountered by those marginalized due to their gender and sexuality.

In their efforts to design programs across various marginalized communities, Raj initially envisioned using the QACP program as a reference. However, they soon recognized the underrepresentation of historically marginalized groups in the mental health field. In response, MHI began exploring how they can support more individuals from marginalized communities in becoming mental health professionals. To this end, they developed affirmative hiring practices, and today, a portion of MHI's team comprises individuals hired through an internship program exclusively open to marginalized communities.

Raj notes that funders often view LGTBQIA+ issues in a vacuum, which, though well-intentioned, can pose challenges. The absence of a more rounded perspective on the issues that impact these communities leads to funds being diverted to stereotypical LGBTQIA+ causes such as HIV/AIDS. Raj emphasizes that without an LGBTQIA+ lens in philanthropy, funders inadvertently hinder LGBTQIA+ individuals from accessing the support they aim to provide. “Consider supporting education without this lens—what happens to queer and trans children? They may end up dropping out of school. And when it comes to conducting sexual and reproductive health lessons, how can we truly address the needs of these communities without such a critical perspective?”stresses Raj.

Raj Mariwala and the MHI team at their head office in Mumbai

Navigating the Journey: Challenges and Learnings

Although Raj’s cogent philosophy on mental health and philanthropy may make it seem like they’ve always had it all figured out, their journey as a philanthropist has not been without its fair share of challenges.“Philanthropy has been a lonely space,” Raj says. “Since there aren’t many philanthropists funding mental health, it feels like my opportunities to learn different approaches to philanthropy have been limited.” As a funder who wants to ensure that mental health philanthropy does not uphold ableist dominant narratives, Raj senses a lack of philanthropic mentors to learn from.

MHI has always believed that in an ideal mental health ecosystem, community leaders would drive mental health work in their own communities. But Raj observes that MHI only understood how to operationalize this idea after immersing themselves into the field. “We now fund a lot of community-based organizations who traditionally did not work on mental health. So we had to slowly learn how to operationalize our vision by understanding mental health alongside them.”

Through MHI, Raj envisions fostering an environment of accessible, affirmative, rights-based, and user-centric mental healthcare and aspires to work on vital initiatives such as suicide prevention, climate change's impact on mental health and deinstitutionalization of mental health institutions.

For philanthropists looking to enter the mental health space, Raj stresses the need to view mental health and provision of relevant services as a human right. This perspective is crucial, especially in a country where people from vulnerable communities living with mental illnesses are often deprived of their rights. More importantly, Raj emphasizes the need to avoid pathologizing mental health, which means using science to fit certain types of behavior into disease models, thereby labeling non-normative genders and sexualities as disorders or illnesses.

But what does recognizing mental health as a rights-based issue look like in practice? Raj explains, “We cannot sidestep the need to address the social, economic, and institutional exclusion that contributes to psychosocial distress. This means that we must widen the ambit of mental healthcare beyond affirmative mental health services and policy to demand freedom from violence and food insecurity and the provision of social safety nets, labour rights, LGBTQIA+ rights, and human rights.”

As India approaches 100 years of independence, there is a critical role that philanthropy needs to play, and as Raj highlights, “We must guide ourselves with the principle that none of us is free until all of us are free. Indian philanthropy has a ready-made blueprint that we need to follow, set by one of India's greatest leaders - Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar. His thoughts on democracy and development are not only globally relevant but are also clearly linked to the tangible pursuit of India achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.”

Inspired thinking presented by

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE