For Ranjit, one of the central challenges is the mismatch between what ecosystems need and what traditional metrics are designed to capture. “Our financial systems value what we can count, not what truly counts,” he says. Philanthropy, he argues, must move beyond output-driven reporting and toward integrated accounting — where ecological indicators such as soil health, water tables, biodiversity recovery, and cultural vitality sit alongside conventional financial measures.

“What if every balance sheet included trees saved or ecosystems restored? What if every rupee earned was assessed for its ecological footprint?” This is not just philosophical; it shapes how the Balipara Foundation operates. With a lean core team and about eight percent of spending dedicated to administration, the organization functions as a distributed ecosystem rather than a single headquarters-led entity. Researchers, community leaders, field teams, and partner institutions collaborate across landscapes reinforcing his belief that systems change cannot be centrally orchestrated, only collectively stewarded.

Raising capital for this kind of work, however, remains one of philanthropy’s blind spots. Many philanthropists are more comfortable in funding visible, time-bound interventions than the slower, non-linear work of ecological regeneration. Issues like salamander habitats in Nagaland or wetland restoration in Manipur can appear niche or intangible to funders accustomed to metrics tied to cost-per-beneficiary or measurable “lives impacted”. “Regeneration doesn’t follow linear metrics,” Ranjit says. “You can’t quantify a forest’s soul.”

Climate volatility has made these gaps more urgent. In recent years, unprecedented flooding in the Eastern Himalayas has undone months, sometimes years of restoration work. For Ranjit, these events are reminders that philanthropy in fragile ecologies demands humility, patience, and models capable of absorbing shock. As he puts it, “You can replant a forest, but you also have to rebuild people’s relationship with nature and with hope.”

As conservation efforts begin to generate income, whether through agroforestry, payments for ecosystem services, or nature-based enterprises, communities are initiating new conversations about fairness and governance. They are asking how benefits from restored forests should be shared, who gets to decide how income is reinvested, and how local enterprises can expand without tipping into extractive practices. These questions signal a shift from conservation as subsistence to conservation as self-determination. Communities are no longer passive participants in development models; they are increasingly asserting their right to shape them.

This transition also places new demands on philanthropy. It requires funders to consider how to support rising aspirations without encouraging a replication of urban materialism, and how to define “a better life” in ways that move beyond higher consumption or visible assets. For Ranjit, the answer lies in reframing aspiration itself. “A good life,” he says, “is one where people have dignity, connection, and purpose.” In the Northeast, where ecology, culture, and identity are deeply intertwined, this becomes a practical guide for what philanthropy should measure, prioritize, and ultimately value.

Lessons from a Life of Giving

After decades of work across industries and causes, Ranjit distills a set of principles he believes new philanthropists must internalize early. At their core is a simple truth: systems do not shift through prescriptions, but through participation. “You cannot prescribe change. You can only co-create it.”

For him, this means entering a field with respect for what already exists — the people, institutions, and knowledge systems that have shaped a landscape long before philanthropy arrives. Rather than seeking to build from scratch, he urges funders to strengthen what is working, fill structural gaps, and collaborate without competing for visibility. In a region as complex as the Eastern Himalayas, the most durable solutions come from aligning with local leadership, not superseding it.

Ranjit is clear that meaningful giving demands discomfort: the willingness to unlearn, to sit with ambiguity, and to recognize that the “right answer” may not reveal itself quickly. “If your giving feels easy,” he says, “you’re not changing the system.” For him, the role of philanthropy is less about directing resources and more about reshaping one’s own assumptions: about value, aspiration, equity, and growth.

A Regenerative Vision for India

Looking ahead, the invitation before India’s philanthropy ecosystem is clear: to broaden our understanding of prosperity itself. True wealth, Ranjit reminds us, lies in the resilience of the forests, rivers, and communities that sustain us. As India charts its next chapter, it must redefine its notion of capital to include ecological systems, and to embed that recognition into how we design policy, measure progress, and govern our shared future.

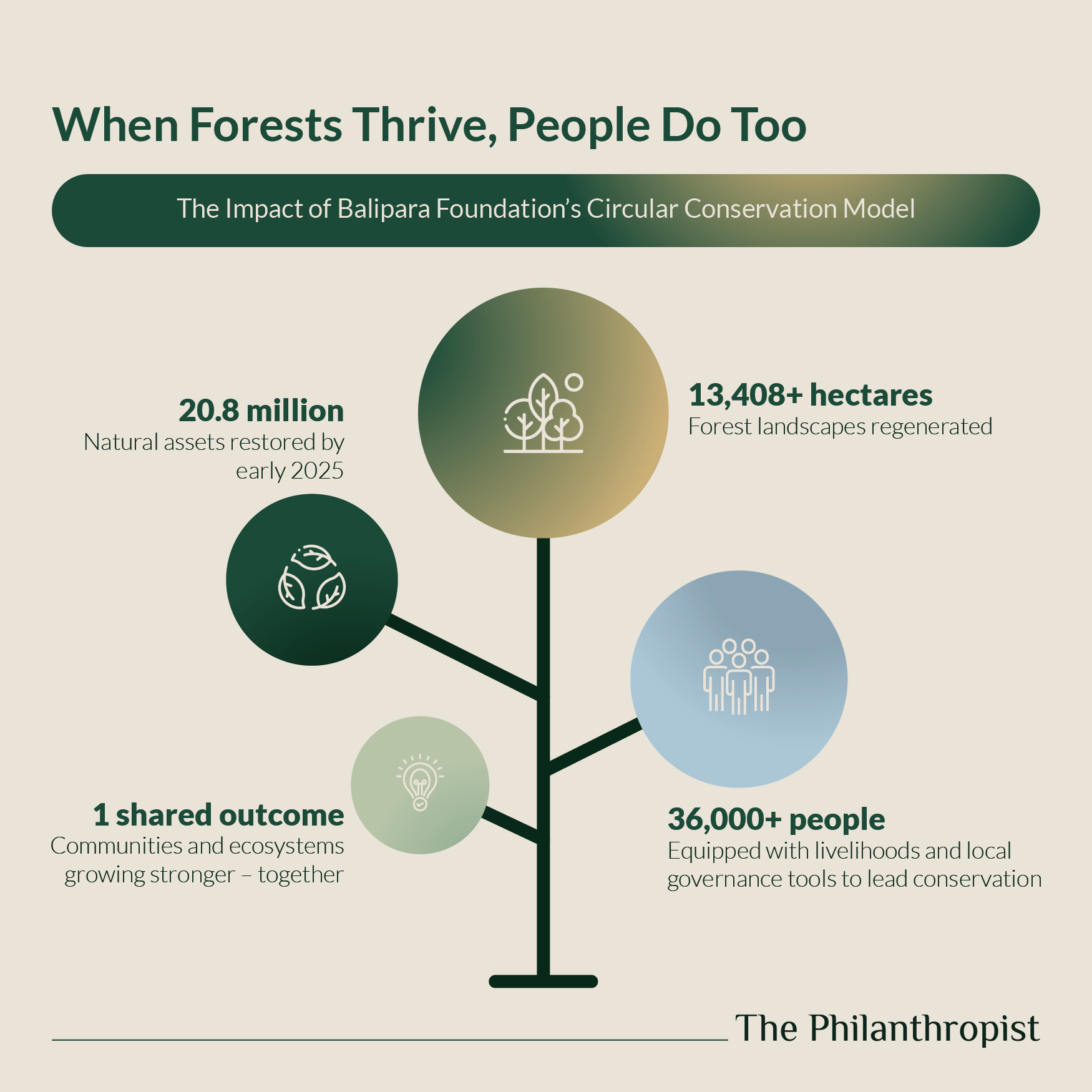

For the sector, this means adopting a regenerative vision, that asks corporations, funders, and civil society to reimagine value chains, invest in nature-positive models, and rebuild our economies on principles of reciprocity rather than extraction. Balipara Foundation’s own journey is but one illustration of what this could look like: a living laboratory where conservation, livelihoods, and culture reinforce one another. But the call is bigger than any single institution.

“The world needs more givers who understand that their own well-being depends on the well-being of everything around them.” The question now is whether India’s philanthropy ecosystem will meet this moment, by funding boldly, collaborating deeply, and choosing regeneration as the foundation of our collective prosperity.

_1028133513.png)