Before entering any partnership, the family applies a consistent set of filters: the founder’s passion and commitment, clean and transparent governance, a clear vision, and a model rooted in real needs. The work they support must be grounded in the lives of the people it seeks to serve, with feedback loops that keep organizations honest about their outcomes.

Meher notes the continuity of values across their worlds: “One of the most important aspects for us has been values remaining constant… governance and transparency being critical… whether it's in business or the NGO world.”

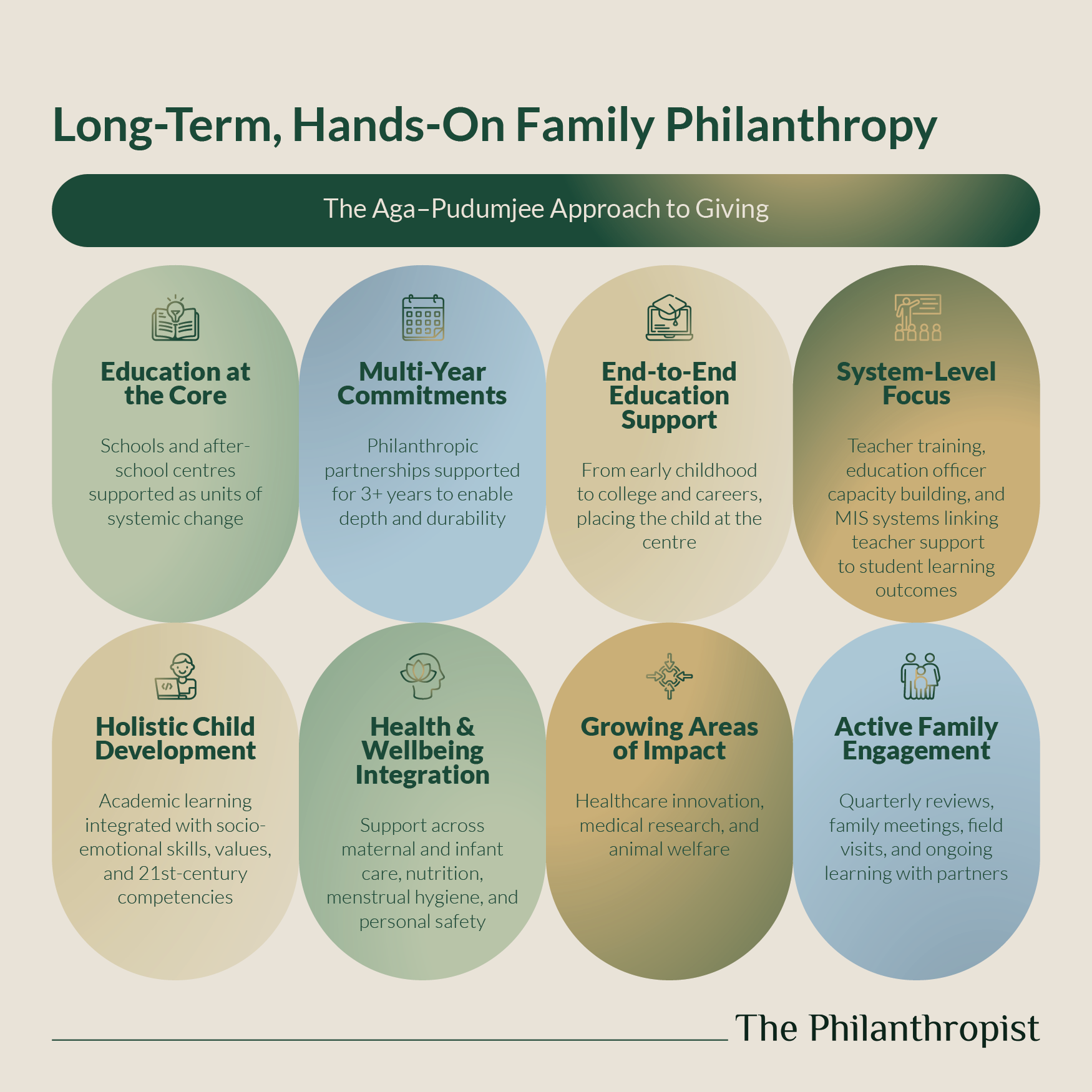

To manage complexity without losing proximity, the family has professionalized its processes over time. Their Head of Philanthropy, Anagha Padhye, anchors this effort — coordinating quarterly reviews with NGOs, internal meetings, a family philanthropy newsletter that captures on-ground stories, and occasional family field visits. She also creates learning spaces for organizations working in similar areas, so that they can learn best practices from one another.

It’s what intentionally prevents the family’s focus areas from becoming isolated, helps them stay collectively informed, with each member remaining deeply aware of what the others are building. It’s how learnings from education inform thinking in healthcare, and how insights from animal welfare sharpen questions around governance and community engagement elsewhere. The intention is permeability — ensuring that knowledge, questions, and accountability travel across causes, even when focus areas remain distinct.

Lea is direct about what accountability means in practice. “There have to be very clear-cut goals, very clear monitoring. And if they’re not able to meet those goals time and again, then we need to re-evaluate, which we would do in business as well.”

Pheroz echoes the role of structure in preventing drift. “When it comes to getting a business mindset into philanthropy, it helps bring structure. Otherwise, you’re spreading yourself thin by doing things all over the place. It’s important to start inside, see locally what you’re doing and the impact you’re making, and then think about replicating that model elsewhere.”

The Road to 2047

By the time the Aga–Pudumjees began thinking about 2047, their conclusions were already narrowing. Decades of working across education and healthcare, and more recently in animal welfare, has taught them less about what philanthropy could do than about where it consistently falls short. The question for them is no longer how to grow faster, but how to grow responsibly — and when philanthropy needs to step aside, so that systems can step in.

Their view of the road ahead is shaped by one central conviction: scale without collaboration is insufficient. Depth, rather than spread, is what creates the conditions for meaningful reach. For Anu, this lesson emerged early and has only sharpened over time. “I would like to go into meaningful depth in the areas where we are,” she says, “and collaborate with other NGOs in the same sector, so that we can widen our reach. Because no amount of philanthropy can reach the whole of India. It can only happen if we have effective public–private partnerships with accountability.”

That understanding frames how the family thinks about systems rather than projects. Meher Pudumjee often returns to the distinction between activity and change — between funding initiatives and shifting outcomes. “Imagine the amount of money that is coming into this sector,” she says. “How can everyone come together to actually change the social landscape, instead of just funding projects?” For her, progress is visible only when it alters lived realities: whether girls stay in school longer, postponing marriage; whether compensation norms shift; whether organizations are allowed to build reserves without suspicion. Project Setu, the Akanksha-led program operating across 100 government schools, is one such example — designed not as a high-touch intervention, but as a model that strengthens teachers, school leadership, classroom experience, parent participation and socio emotional learning within existing public systems.

Pheroz emphasizes structure as the road to scale and collaboration. Years of working at the intersection of operations and outcomes have convinced him that we should be looking at things in a more scientific and structured way. “Why hold on to data? Why not share it?” For him, too, government platforms, when engaged seriously, can act as force multipliers, particularly in areas like healthcare, where prevention remains far more effective and economical, than cure.

From the next generation, the concern is less about direction than about how the sector functions day to day. Lea and Zahaan point to the structural habits that can limit collective impact: fragmented efforts, parallel models developing in isolation, and limited incentives for collaboration across stakeholders. Lea often returns to a central question — how can conditions be created for organizations working in similar areas to learn from one another and move together? Zahaan adds that this requires periodic reassessment: sharing what works, letting go of what doesn’t, and adapting parameters as contexts evolve.

Taken together, the family’s view of 2047 rests on a few hard-earned beliefs learnt through a steady value system: that building institutions matter more than isolated initiatives; that collaboration is slower but unavoidable, and in fact, encouraged; and that time spent — with patience, discipline, and by sharing it — is philanthropy’s most underused resource. Their own giving reflects this posture: staying close to the ground, sharing what works, holding themselves and their partners accountable, and resisting the temptation to confuse activity with progress. Their philanthropy is the practice of these principles. In a country as large as India, they see their work as “a small drop”. What matters to them is how deliberately this drop is placed.

_1891054289.png)

_508391263.png)