Sunil Wadhwani traces his philanthropic impulse first to inheritance and memory. “I’m from Sindh,” he says, situating himself within a geography shaped by historic displacement. His maternal grandfather was the Surgeon General of Karachi, who later became the mayor of Karachi. His grandfather on his father’s side was a headmaster who ran the largest school in Sindh. “Even in those days — about 100, 120 years ago — they were setting up schools for women from low-income households,” he recalls, with a particular emphasis on education for girls and women, “because that was challenging at that time. I’d heard these stories growing up.”

But the impetus to give came much later. Sunil had grown up in India, studied at IIT, moved to the US, and built companies — first unsuccessfully, then with growing traction. His first venture, a healthcare medical device company, failed. “Five years after I started, it went down the tubes. I lost my life savings and so on,” he says lightly. The second company did better, informed by the lessons of the first. As he prepared to take it public, flying between coasts to meet fund managers, something shifted. “It just hit me how fortunate I’d been,” he says. “Being born into a middle-class family, post-partition, at a time when 90% of the people in India were poor.” Even more unusually at the time, his family was English-speaking. “I’ve just been very lucky — pure, random chance, the family I was born into. I could have been born a quarter mile away into a different kind of family, and life wouldn’t have been quite the same.” That awareness, sharpened over time, would later shape how he thought about deploying technology back home, particularly in sectors like healthcare and agriculture, where scale, trust, and everyday usability determine whether innovation holds. His own opportunities drove Sunil to want to do more for those less fortunate.

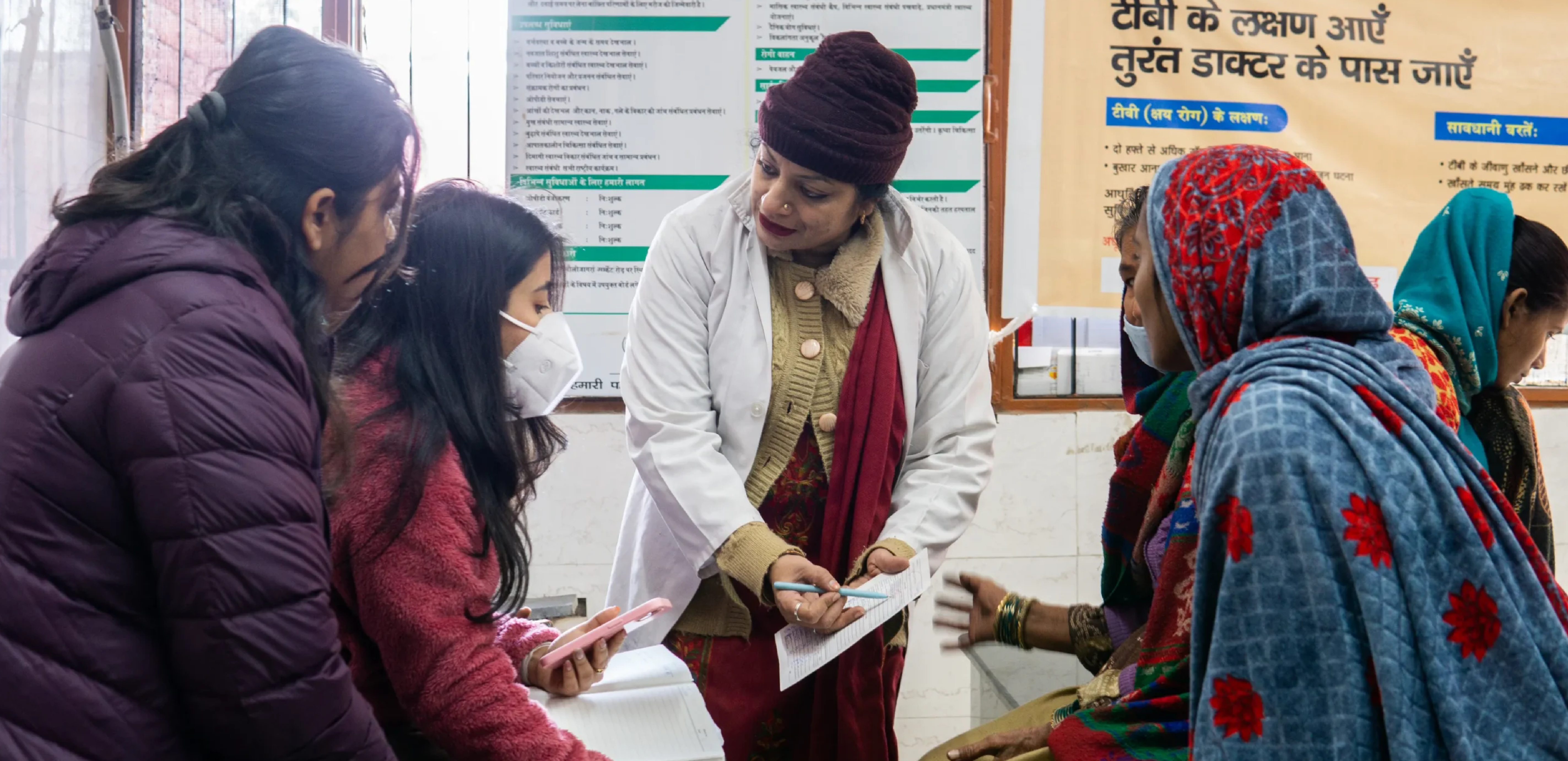

His first instinct was to work with NGOs in India’s healthcare sector, supporting capacity building and program expansion. “I was saying, ‘You’re doing a great program in 20 villages, how do we make it 50, how do we make it 100?’” Over time, however, he began to see that scale was shaped as much by context as by commitment. Many NGOs, he found, were doing deep, careful work within complex local realities, but were operating inside funding cycles and delivery models that limited expansion. “Many years later, though, I found that these NGOs, well-intentioned though they were with hard-working people, scaling was an issue for them. So finally, 10 years ago, I said, let me try and do this myself.” He began by setting up a public health initiative to strengthen primary healthcare systems, stumbled repeatedly, and learned where ambition exceeded reality. “The stuff that I thought would work absolutely didn’t work for the first couple of years.” What came, however, was a more grounded understanding of scale itself: “how you work with government, what you do, what you don’t do.”

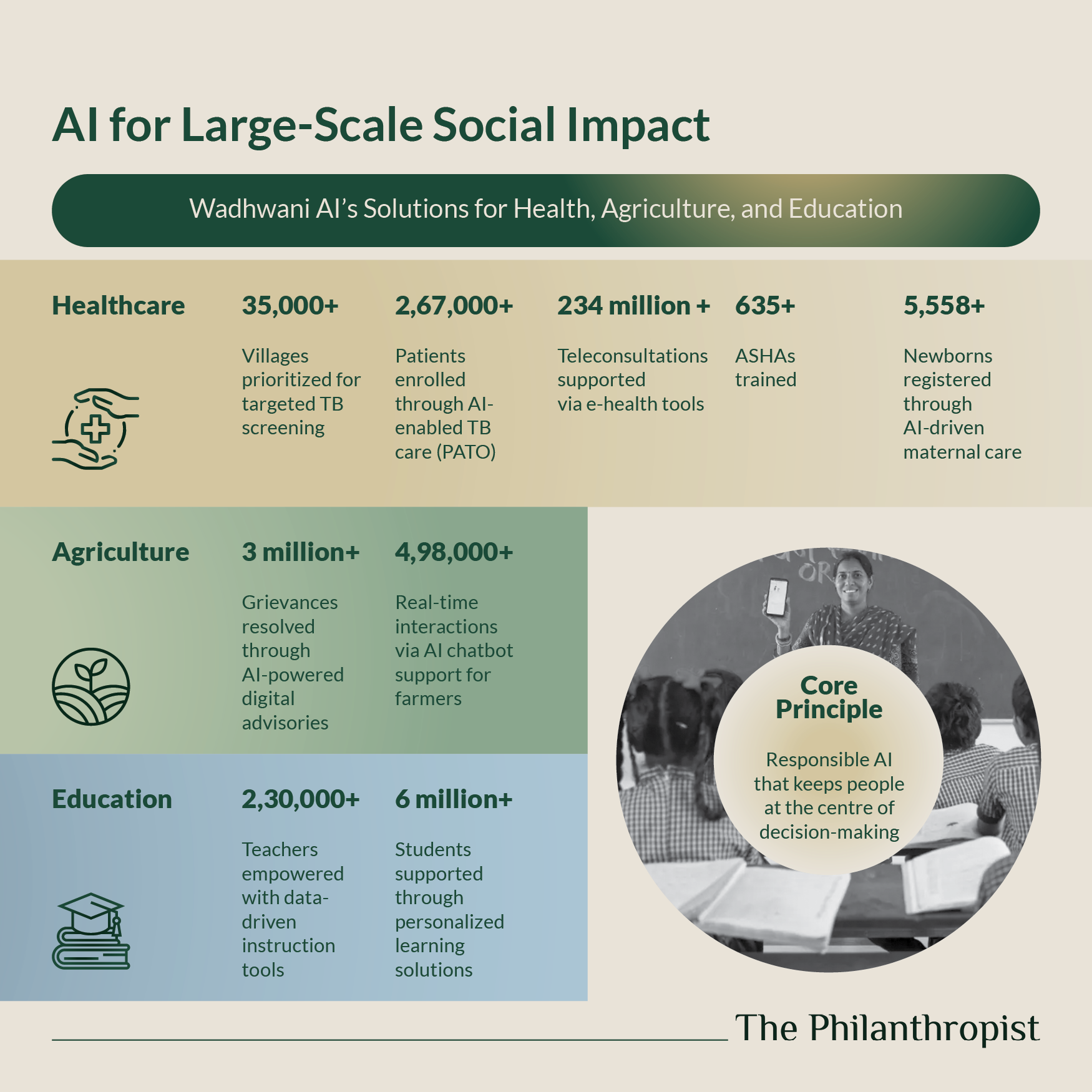

Around the same time, as a trustee at Carnegie Mellon, Sunil was asked to help chart the university’s future. Surrounded by people who were developing AI well before its current prominence, he noticed a gap. “I could now see tens of billions of dollars going into AI research. But all of it was going into commercial research.” After confirming that the gap, in fact, did exist, the question became unavoidable: “How do we use AI to help the bottom 3 or 4 billion people in the world who make less than $5 a day?” The answer, eventually, was to build what did not yet exist. “I went to my brother,” recalls Sunil, “who has his own foundation, I have my own foundation. We're both believers in technology. He's also a tech entrepreneur. And I said, ‘Why don't we do this together?’ And he said, ‘Great.’” So, it came to be that six years ago, with his brother, Romesh Wadhwani, Sunil set up Wadhwani AI as an institution designed to apply AI where the market had not looked.